Water of Life is an art-science collaboration between Rob St. John and Tommy Perman exploring flows of water through Edinburgh using drawings, photos, writing and sound.

Water of Life is an art-science collaboration between Rob St. John and Tommy Perman exploring flows of water through Edinburgh using drawings, photos, writing and sound.

I was suitably intrigued when I found out that Rob and Tommy were teaming up for the project. They are both multi-talented artists who have contributed a lot to the music and art scenes in Edinburgh and beyond.

Rob makes music under his own name and as part of eagleowl, as well as writing for the likes of Caught By the River. Tommy was up until recently a member of band and art collective FOUND, produces art/illustration as Surface Pressure and recently released an EP under the name ComputerScheisse.

I hope that introduction has whet your appetite. Now, here are a few probing questions about the project’s creative flow.

How did the Water of Life project come about in the first place and what were the main aims of the project?

Rob: Tommy and I had worked on a few things together before, and had found that we had shared interests: the overlaps between art and science; finding new ways of exploring, seeing and thinking about the city.

Creative Scotland’s ‘Imagining Natural Scotland’ fund was announced in the Spring, and we put the project together in response to the call: thinking about what we term ‘natural’ in the Scottish (and wider) landscape, and how this ‘naturalness’ has been imagined and reshaped, both literally and metaphorically through time.

Tommy: I’d previously worked with Rob on a handful of different music and art projects. I had been a huge fan of Rob’s music and at one point his live band were my favourite act in Edinburgh (they only lost that esteemed position as Rob moved away to Oxford).

We definitely share a bunch of interests across art, design, music, photography and science. Rob spotted the opportunity and suggested we put in a proposal. We met up a few times, chatted and the idea for Water of Life emerged pretty quickly.

Did you both share a fascination for Edinburgh’s watery past? Why did you choose to explore this topic in particular?

Rob: Water was a great focal point for exploring the city, in the way that it was been constantly reshaped and managed through history: streams culverted off underground into sewers; lochs drained and refilled; the water itself constantly changing, from filtered to polluted; connecting our selves with pipelines through our houses, the water in rivers, lochs, sewers, drains, sanitation plants.

As well as asking questions about what we term ‘natural’ or ‘wild’ in the city, traces of water often reveal interesting conduits into Edinburgh’s past. Street names often echo watery histories. In Edinburgh this includes: historic water supplies (Fox Spring Avenue and Swan Spring Avenue are both named after springs at Comiston that first fed the city in the 17th century); lost lochs (Boroughloch at the edge of the former loch on the Meadows) and industry along the Water of Leith (Tanfield, Bleachfield, Ladehead).

Tommy: For a while before we began this project I’d been interested in the Edinburgh sewage works down at Seafield. For those who know my visual artwork, I’m very interested in the less well documented details of city life. I had become fascinated by Seafield because visually it looks completely different from anywhere else in Edinburgh. There’s some wonderful, industrial buildings and large scale pipe work visible from the perimeter fence.

I’d also been looking at satellite images of Seafield on Google Earth and loved the repeating circles of the water treatment pools. So when we embarked on this collaboration I was already thinking about the kind of life support systems a city needs to sustain its inhabitants and I think we both took that as a starting point and followed it in different directions.

How did the collaborative process work? Did you agree on specific roles?

Rob: We worked as collaboratively as possible, taking off on field trips across Edinburgh’s water network, from the grand Talla and Megget reservoirs in the Borders, which together provide much of the city’s drinking water, to the Seafield Sewage Works, where much of the city’s water ends up, sullied and full of dissolved excess. The trips would be exploratory, taking in sound recordings, photography and note making.

For example, we went to the Glencorse reservoir in the Pentlands, interested in the new sanitation plant, and the 19th century reservoir. Denied access to both (a common theme in the project, raising other questions), we happened upon the old filter beds below the reservoir – now overgrown, with the remnants of the industrial process now mingling with encroaching nature, giving the impression of a landscape art installation.

Tommy: I think we were aware of each others strengths so there were certain tasks that we divided up. Rob is very good at researching a subject and spent a lot of time in various libraries across Edinburgh uncovering amazing stories that I definitely wouldn’t have found on my own. Rob also did the bulk of the writing as it’s a skill that comes easy to him. I like writing but it tends to tax my brain a lot – especially since becoming a dad early this year – I find it very difficult to focus long enough to get the words down.

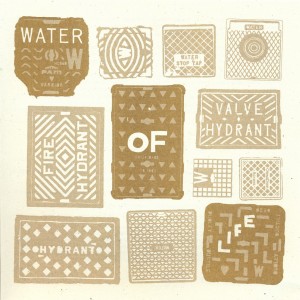

I took charge of researching how we were going to produce and manufacture the records, folder and prints. And I did most of the design and drawings. But even in these areas we collaborated – making suggestions and offering each other our opinions.

Did anything unexpected come out of the collaborative process or the research?

Rob: We set off with an exploratory remit: to work collaboratively, drawing from elements of artistic and scientific practice; to attempt to trace ideas of what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ regarding water in the urban environment. As a result, most of the stories we discovered were new and unexpected, and we ourselves found new ways of seeing and understanding a city we’d both lived in for a considerable amount of time.

For example, in the car park of office buildings by the Seafield Sewage Works sits a glacial erratic boulder, the Pennybap. This boulder is said to be inhabited by a Shellycoat, a water-based spirit, yet is neglected and off-limits, a blend of the folkloric, historical and industrial, perhaps a good metaphor for how we view and use water in the city.

Tommy: Although we submitted a detailed funding proposal with fairly concrete outcomes, I had no idea what the content of our project would be. I really enjoyed allowing our research and the materials we gathered on field trips to inform the artwork we produced at the end of the project.

I didn’t expect us to write so much music – in fact at the beginning of the project we weren’t sure if the audio component would be just field recordings or something else. I also hadn’t anticipated that we’d use film photography and that the results of the photos we took would be so unusual (my pictures came back from the developers marked with random vertical streaks which at first disappointed me but then I realised totally added to the images).

A few things that stand out to me from perusing the website are the attention to detail that has gone into both the research and the artwork, including the packaging etc. Would it be fair to say that this is an integral part of both of your approaches to your creative work, and could you both say a little bit about why that’s important to you?

Rob: Yes, it’s an important part of how we both work, I think. From my perspective, it’s important that every bit of creative output has a number of tangents that you can follow out: links, histories, sites. We’ve created the release of a 7″, prints and essays in a letterpressed folder. All aspects of the production process have been chosen to minimise their environmental impact: the vinyl, paper and card used is recycled, the essays and prints printed with soy inks, and the letterpress with existing type and a teaspoon of ink for 300 copies.

Part of the motivation for this process was to try and show that it is possible and (reasonably) affordable to incorporate ideas of environmental impact into your production process for projects such as ours, which can hopefully be used as inspiration for others wanting to do similar things.

Tommy: I’m very happy that you’ve noticed this! I think my parents would tell you that I’ve always been interested in fine details ever since I started drawing as a young child. But in recent years I have wondered if it’s really necessary to put quite as much detail into each project. I know you’re aware of my previous collaborations with FOUND, in our last project #UNRAVEL we produced 160 pieces of music for the installation. My collaborator Simon pointed out that it’s very possible that a number of these songs will never be heard. I felt a bit crestfallen when he mentioned this.

It’s clear I really enjoy the process of creating artwork but my intention (and hope) is that there will be an audience for it. Working with Rob was potentially quite dangerous for producing work with such depth of detail that some might be lost. We both have this tendency to really think the details through to a ridiculous degree. When I was working on the audio production for the music I kept asking myself if I could justify the choices I was making within the limits of the project. I desperately wanted every element to feel like it belonged.

The project was funded by Creative Scotland – presumably without that funding it wouldn’t exist at all? Do you have any advice for other artists who want to pursue funding for their projects?

Rob: We’re grateful to the ‘Imagining Natural Scotland‘ fund for making this work possible. Tommy and I would have most likely collaborated anyway, but the funding allowed us both to experiment and to address every aspect of the project as we wanted: from research to manufacture, allowing us time for reflection and the ability to address environmental impact in every aspect of the production process.

Tommy: It is amazing to have a budget to work on a project like this and produce a 7″ vinyl with some pretty lavish packaging. These kinds of opportunities don’t arise very often so when they do I think it’s best to make the most of them. I think we have and I’m convinced we got a lot for our budget.

The Water of Life limited edition 7″ is now available to pre-order from bandcamp. It is limited to 300 copies, and will be released on 9th December 2013. The package includes a letter-pressed folder on recycled card, a 7″ record pressed on recycled vinyl and a set of essays by Rob and prints by Tommy exploring the themes of the project, riso printed using soy inks on recycled paper. It also includes digital download of the music.

Tommy and Rob are giving a short talk at Analogue (bookshop, Candlemaker Row) on 7 December. It’s a small space and there weren’t many tickets left at the time of publishing, but if you’re quick you might be lucky enough to get the last few tickets. More info

One reply on “Water of Life: Interview with Rob St John and Tommy Perman”

[…] Scotsman, 5th December 2013 Clear Minded Collective, 28 November 2013 Decoder Magazine, 21 November 2013 The Scotsman, 6th November 2013 The Herald, 6th November […]

LikeLike